The non-alcoholic wine debate still rears its ugly head from time to time, centering on the question whether non-alcoholic wine or any other substitutes could be permitted for use in the Sacrament. At times I have found myself engaged in a exchanges in which I found it necessary to defend things which ought to be beyond question among Lutherans.

One such exchange took place in a little tete-a-tete I once had with a proponent for the use of grape juice. It was at an open hearing of a floor committee for a district convention of the LCMS. The meeting room was far too small, as the floor committee saw a great multitude in attendance. The walls were not visible for the flesh that lined them, and the summer heat was no ally to that flesh. I arrived about ten minutes after the hearing began, so with a number of others had no place to sit. By this default I ended up standing in a highly visible place right behind the chairman's seat, and listened as the arguments for and against non-alcoholic wine were heard. On the one side of the debate were those of confessional acumen and concerns who pleaded for the maintenance of right administration of the Sacrament in accordance with Augustana VII, on the other side were those who contended for what they called the need for love and understanding in dealing with difficult situations with alcoholics and the like.

In the midst of all this there was a certain layman among the latter, who gave a long, passionate speech about his days in the service in the Korean War and World War II. He spoke with feeling about the 9,000 soldiers who lost their lives fighting beside him at Omaha Beach. Before they went to their final battle, these men all received "communion" from the chaplain, who, due to scarcity of resources, did not have enough wine. But he did have grape juice (why this is so, no one asked). So grape juice they all received, and went on into battle, and lost their lives. At this point the man asked for a pastoral reply to the question he posed: "Do you mean to say that those men did not receive the forgiveness of sins?"

It was then that I opened my mouth, and gave my reply which raised and rankled more than a few eyebrows and feathers respectively. I said but one word, which all in the room clearly heard, and which for its piercing simplicity shook the very foundations of that chamber: Yes.

That was my pastoral reply.

At once another man lunged at me, crying out angrily, "Lawyer! Pharisee!" The committee members, thankfully, were livid against this name-calling, insisting that it stop.

Debate continued in that crowded room until finally there remained time for one more speaker, and the chair yielded to me.

"I must tell you," I began my defense, "that it was I who got this whole mess started, for I am the author of the resolution in its original form. I wrote it against non-alcoholic wine; but I certainly never expected such a brouhaha to result, and I cannot even recount for you all the names I have been called since I brought it up.

"It has occurred to me, however, that the reason there is such passion over all this, is possibly a failure to remember a crucial distinction, which Martin Luther so clearly made in his Galatians commentary. I know it by heart, for it is very important to me. Luther carefully distinguishes there between faith and love, and warns against forgetting the distinction. Love, says Luther, always gives in, always lets others have their way, always gives place. Love bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things. But not faith. Faith will not stand for anything. When it comes to faith (says Luther) I want to be stubborn, and to be known as someone who is stubborn. Faith will not yield the least little bit. Here is where I side with Luther, then, and say the same, that I too wish to be known as someone who is stubborn about the faith.

"For this matter runs to the heart of the Gospel. Certainly those 9,000 servicemen who died were either saved or not, depending alone on their faith in the Gospel. But at that moment, when that chaplain gave them that grape juice, they were not receiving that forgiveness. This is why this matter is so critical. This is not lovelessness or legalism. It's the very opposite; for this has to do with Christ. Those servicemen needed one thing there on that battlefield, for their confidence and comfort in time of trouble, and no amount of good intentions (with which the road to hell is paved) could give them what they needed. They needed Christ whom they believed, but the chaplain did not give Christ to them.

"It's really very simple, and I plead with you to listen to me now: If you change the elements of the Sacrament, you don't have the Sacrament, and if you don't have the Sacrament, you don't have Christ."

So ran my reply.

On the same day there were some who expressed concerns with that original retort of mine, that “yes”; not, that is, with its substance (though indeed many were quite opposed to that as well), but with its fittingness in that time and place, the simplicity of it. No, I was told, that turned people off, made them unnecessarily angry, and could have been expressed otherwise. I was at that moment too harsh, some said, and that was wrong.

Now I admit to having thought about this long and hard myself. Was that “yes” too much? Should I have let the rhetoric pass unanswered? Could I perhaps have done more through a more winsome approach, something less barbed? Was that answer less than pastoral? Now clearly it would be easy for me simply to say that it was, and admit a lapse of self control there. Strangely, however, my conscience, which is so often a noisy gong in my ears, was quite silent and at peace.

The reason I could admit error there is that I came to the conclusion not only that I did not err, but also that very much more is at stake in this matter than any admission of my personal wretchedness, of which I am always well aware. Certainly (because of that wretchedness) I am one who can easily fall to the desire for vainglory, and certainly also from this to self-aggrandizement in the eyes of my peers. But here I must divide and distinguish sin from faith; for though I sin, yet do I believe, and further believe that in that assembly “yes” was absolutely required, notwithstanding any sin which may have attended it. It is when I consider the alternatives carefully that this becomes most clear.

To have said nothing would not have been the way of faith; this is not to say it was necessary that I be the one to answer, merely to say that faith must answer this question; somebody had to answer, lest through silent acquiescence on the part of all the gainsayers make disciples and, as it were, Goliath taunts the armies of God unanswered. What figures more importantly in the rejection of this option, however, is faith's simple necessity of making confession.

There are times when a clear confession is called for, times when men of faith must say, "I believed, therefore have I spoken." Such speech comes not from reasoned considerations of effectiveness, nor cautious regard for winsomeness. Indeed the word sprang from my lips before I gave a single thought to the effectiveness it might have. I simply knew it needed saying, at once, before the opportunity for saying it passed by.

But one might as well say this was not the time for such confession, that this was not the place for true theological discussion, for the room was too hot and crowded, and passions ran high, etc. To this I would reply that these kinds of circumstances are not in themselves prohibitive of confession. If they were, then not only would every man who spoke well that day have been out of place (and there were a great many who spoke well for the faith on that day and in that place), but even Luther's famous confession before the Diet of Worms would have been out of place. For Luther's confession was likewise in a small upper room which was so full of officials that crowd control became necessary; indeed emotions and tensions ran so high that pandemonium broke loose there following Luther's confession (see Schwiebert, The Life and Times of Martin Luther, 501-505). When tempers or passions are inflamed, certainly it is more difficult to make reasoned judgments, but the increase of difficulty in itself cannot justify the shutting of confessional mouths.

Moreover, and most importantly, if this was not the time for such confession, when is the time for it? The Church is not of the world, but she is in the world, and she is required to make her confession before men, as our Lord Himself declares. Reason, whom Luther was wont to call the devil's greatest whore, cannot be trusted to determine the circumstances most fit for such confession. This must be left to faith, and faith must be left to itself to make such judgments. Faith, molded and led by the Word, employs that Word in confession when and where it wills, and is alone fit to determine when to speak, especially in the heat of battle. Faith employs reason in this regard, to be sure, but reason cannot question faith, for faith knows more than reason can fathom.

Thus I conclude that it was fitting and meet for faith to speak there and then. But what would faith say?

The question itself wanted a simple yes or no answer. Did those 9,000 receive forgiveness at Omaha beach? Here we must consider the enemy's treachery. How perilous is the ground of this battle, where the enemy vies for the hearts of the careful hearers witness to that debate.

What if I had said “no”? What would it have meant? Here the enemy could have taunted the people of God. Aha, aha, he could then well have sneered, your insistence on right administration cannot stand here! See, you answer “no” to my question, so you must admit that I am right, for if those 9,000 received forgiveness there, then why have you made such an issue of this matter? How can you make such a big thing out of such a small thing as this? For they died with forgiveness, the one thing needful.

But did they? One could (with the sophists) determine that even though they did not receive forgiveness with the cup, yet they did with the host, which was bread, and hence also the body of Christ. But this skirts the true question, which in the first place was not asked concerning the host but the cup, and in the second place was in substance asking whether changing the elements affects the giving of forgiveness through them.

But what about the Word? Could we not say that they certainly did receive forgiveness with the words of the Gospel spoken then and there over the elements? Is it splitting hairs to say that forgiveness was not received in the cup as well as with the cup?

Here we have come to the very heart of the matter. For if forgiveness was thus received, the very Sacrament has been robbed of its essence. The words of the Gospel tied to the Sacrament are these: This is my blood . . . shed for you. It is true that Christ's blood was "shed for you", and that that is itself the Gospel; yet these words now come in a declaration that makes this, namely this cup, meaning by circumlocution the wine in this cup, His blood, "shed for you." Thus in the Sacrament we say that this cup is that blood, and recognize that the Gospel itself is placed nowhere else than in this cup. Therefore to alter what is in the cup is to remove the Gospel from it, and hence also forgiveness.

But surely, one might still protest, you do not mean to say those 9,000 servicemen died in their sins. To this I reply with Luther and Augustine that certainly faith's desire for the Sacrament is in itself sufficient: "only believe," they both declare, "and you have already received the Sacrament."

But what did they believe? That the blood of Christ was under the grape juice? Here I must sincerely hope not, for this is not the substance of faith! Faith has no word of Christ here upon which to rely for a conviction that the blood of Christ was under the grape juice, for Christ gave no promise regarding grape juice. Such faith is a sham and folly. My pastoral heart most sincerely desires with God that no one be condemned, least of all 9,000 servicemen who lost their lives in valiant service to their country, and I can share with Francis Pieper the fervent hope and expectation that through a felicitous inconsistency they retained a saving faith while at the same time holding externally to this demon's doctrine regarding grape juice.

Nonetheless in the answer to the question posed very much is now quite clearly at stake.

But how cleverly was the question posed. For one who answers “yes” opens himself to some very clear perceptions of lovelessness against those poor 9,000. So the devil taunts: See, I have shut your mouths! You cannot reply, your tongues are shackled!

(Yet I believe it was also divine providence that saw the question posed the way it was, in order that the truth may be affirmed with a “yes” rather than with a “no” which more than any other word would make one sound negative!)

Thus did almighty God in His mercy loose my tongue; thus did He open my lips, that my mouth might shew forth His praise. “Yes!” did I cry; and would again cry, nine thousand times, yes. Yes, for it is not lovelessness which insists here, as many may falsely suppose (many are my persecutors and mine enemies); rather, it is the knowledge that the enemy was at work here, stealing by treachery the Church's most precious and sacred Treasure. Yes, without the Sacrament you are without Christ. Yes, you may not have Him according to your whims and wishes, no matter how fiercely you desire Him on your own terms. Yes, He comes on His own terms and none other. Yes, though all the world should rail against His Word and Testament, yet will I affirm and insist that He alone is true and every man a liar. Yes, where His Testament is kept whole and intact, there and nowhere else, is His forgiveness and mercy distributed to poor and needy sinners. Yes, you must take Christ as He gives Himself and in no other way, for otherwise you shall not have Him at all, as the doctrines of demons quickly invade and snatch you away. With my yes and amen do I therefore affirm this truth.

But for this I did indeed open myself to false accusations, which quickly flew, and wounded me. But an angel of God woke me from restless sleep that night and ministered to me, as I recalled in faith words sweeter than honey to my taste, the words of our Lord and Master Jesus Christ: Blessed are ye, when men shall revile you, and persecute you, and shall say all manner of evil against you falsely, for my sake. Rejoice, and be exceeding glad: for great is your reward in heaven: for so persecuted they the prophets which were before you.

So I rejoice in this faith and confidence, and in the knowledge that the greatness of reward shall be inversely proportionate to the worthiness of His servant.

Material taken from a column published in 1994.

Saturday, May 27, 2006

Wednesday, May 17, 2006

High Church or No Church?

As the fissures widen in the bedrock that once was the stalwart contingent of conservatives in the Missouri Synod, interesting patterns in the breach have begun to emerge. Most prominent of these has to do with the marks of divergent worship practices, marks which designate various strains of loyalty to the perceived tradition. On one side are those for whom worship style or choice is largely a matter of adiaphora, while on the other are marked by their attempts at maintaining a catholicity in appearance as well as in substance.

Borrowing terminology from the Anglicans, people have referred to the choices as "high church" or "low church." Denizens on each side of this fence tend to use the term corresponding to the other side derogatorily. Those of the "low church" mentality consider "high church" to be a negative appellation. This was once largely due to remembrances of "high church" tendencies among the liberals of the seventies who sympathized with those who marched pompously out of the St. Louis Seminary. Those men were high church, they wore collars, they chanted, and they liked to think of themselves as catholic. But those men were also naughty, to couch the matter in this rather blunt term I heard from a faithful if rather cockney lay woman I encountered once on a recent trip to the British Isles: they were naughty Lutherans. That is, they rejected the authority of the Scriptures and were openly given to the excesses of historical criticism; hence "high church" came into use as one way to designate their naughtiness, by those on the low, conservative side of the fence.

Today, however, on the "high" side of the fence, those naughty Lutherans are nowhere to be found. They have flown the coop. But meanwhile others have arisen who, it turns out, look very much like them: they wear collars, they chant, and they like to think of themselves as catholic. The difference is that they are not naughty; they never question the authority of the Scriptures, and they always place themselves humbly beneath that authority. They may dress like the notorious Seminex-arian John Tietjen did, but they are definitely not on the same team. These are men whose confessional subscription, unlike that of the Seminex crowd, is not quatenus but quia; that is, subscribe to the Lutheran confessions not insofar as, but because they believe them to be in agreement with the Sacred Scriptures. Because of that subscription, and because of their allegiance to the catholic tradition which Martin Luther espoused, they are liturgical in their approach, and they tend to view the Missouri elements on the other side of the fence as "low church", in as derogatory a sense as the latter employ the former term against them.

The designations are flawed on both sides. The “high church/low church” jargon is really borrowed from the Anglicans, and if “high church” is meant to designate “high mass,” then it really isn’t high until there is incense, bells, celebrant, deacon, subdeacon, and lots of chanting. “Low church” among the British calls to mind the Puritans with their their anticlericalism and their sacramentarian spite for the means of grace.

Moreover, just as "high church" is weak due to its failure to distinguish the naughty from, as it were, the nice, so also "low church" is weak. There are some among those so designated who are simply following the tradition they have learned, than which they have known no other. But now there are others for whom "low" is employed with a vengeance, almost as a confessional statement against those who might suggest that worship style is something other than an adiaphoron. So much vengeance marks this new version of low, in fact, that one wonders just how low is possible.

Beyond these weaknesses with the terms, there is a more serious weakness, which has to do with what worship is, and how worshippers actually worship. Simply put, I believe, it often has to do with whether one is paying attention or not. Low church, especially among those who employ its distinguishing marks with an adiaphorous passion, all too often means church in which the liturgy means little or nothing. Either portions of it are discarded, or, if employed, are waded through as if in thick mud on the hiking boots of would-be adventurous campers. “See,” they say, “we are out to prove that this is all adiaphora; we can take it or leave it. We may (or may) not put up with some of it, if only to make the hearers good and ready to hear the all-important sermon.”

Such use of the liturgy sees it rather in the same vein as we view a catena of commercials before our favorite television program begins. Thus one may find people and pastors trudging through the liturgy with no particular attention to posture or position, providing subtle indications that they are not really listening or praying along. The sermon often has no connection whatever to the liturgy or even readings, and the pastor may even retire to the vestry during certain hymns or portions of the liturgy for which his presence as "worship leader" is not needed. Certainly there is no bodily indication in such cases of being in the presence of the Incarnate, Risen Christ when at worship.

The widening of the liturgical rift between low and high is therefore making the distinctions more telling than they once were. The vengeance with which "low" worship is now being practiced, as well as the depths to which "low" has in some cases plummeted, leads us to the temptation to wonder how far in fact low now is from the bottom, that is, from the absence of worship at all. Have their efforts to distance themselves from the naughty Lutherans resulted in a reaction also against what is noble and good about traditional Lutheran worship? Put otherwise, perhaps we are drifting to a choice between high church and no church. A sad result, that, of attempts to fend off the naughty, who in fact are already long gone.

Adopted from an article published in June 1994

Borrowing terminology from the Anglicans, people have referred to the choices as "high church" or "low church." Denizens on each side of this fence tend to use the term corresponding to the other side derogatorily. Those of the "low church" mentality consider "high church" to be a negative appellation. This was once largely due to remembrances of "high church" tendencies among the liberals of the seventies who sympathized with those who marched pompously out of the St. Louis Seminary. Those men were high church, they wore collars, they chanted, and they liked to think of themselves as catholic. But those men were also naughty, to couch the matter in this rather blunt term I heard from a faithful if rather cockney lay woman I encountered once on a recent trip to the British Isles: they were naughty Lutherans. That is, they rejected the authority of the Scriptures and were openly given to the excesses of historical criticism; hence "high church" came into use as one way to designate their naughtiness, by those on the low, conservative side of the fence.

Today, however, on the "high" side of the fence, those naughty Lutherans are nowhere to be found. They have flown the coop. But meanwhile others have arisen who, it turns out, look very much like them: they wear collars, they chant, and they like to think of themselves as catholic. The difference is that they are not naughty; they never question the authority of the Scriptures, and they always place themselves humbly beneath that authority. They may dress like the notorious Seminex-arian John Tietjen did, but they are definitely not on the same team. These are men whose confessional subscription, unlike that of the Seminex crowd, is not quatenus but quia; that is, subscribe to the Lutheran confessions not insofar as, but because they believe them to be in agreement with the Sacred Scriptures. Because of that subscription, and because of their allegiance to the catholic tradition which Martin Luther espoused, they are liturgical in their approach, and they tend to view the Missouri elements on the other side of the fence as "low church", in as derogatory a sense as the latter employ the former term against them.

The designations are flawed on both sides. The “high church/low church” jargon is really borrowed from the Anglicans, and if “high church” is meant to designate “high mass,” then it really isn’t high until there is incense, bells, celebrant, deacon, subdeacon, and lots of chanting. “Low church” among the British calls to mind the Puritans with their their anticlericalism and their sacramentarian spite for the means of grace.

Moreover, just as "high church" is weak due to its failure to distinguish the naughty from, as it were, the nice, so also "low church" is weak. There are some among those so designated who are simply following the tradition they have learned, than which they have known no other. But now there are others for whom "low" is employed with a vengeance, almost as a confessional statement against those who might suggest that worship style is something other than an adiaphoron. So much vengeance marks this new version of low, in fact, that one wonders just how low is possible.

Beyond these weaknesses with the terms, there is a more serious weakness, which has to do with what worship is, and how worshippers actually worship. Simply put, I believe, it often has to do with whether one is paying attention or not. Low church, especially among those who employ its distinguishing marks with an adiaphorous passion, all too often means church in which the liturgy means little or nothing. Either portions of it are discarded, or, if employed, are waded through as if in thick mud on the hiking boots of would-be adventurous campers. “See,” they say, “we are out to prove that this is all adiaphora; we can take it or leave it. We may (or may) not put up with some of it, if only to make the hearers good and ready to hear the all-important sermon.”

Such use of the liturgy sees it rather in the same vein as we view a catena of commercials before our favorite television program begins. Thus one may find people and pastors trudging through the liturgy with no particular attention to posture or position, providing subtle indications that they are not really listening or praying along. The sermon often has no connection whatever to the liturgy or even readings, and the pastor may even retire to the vestry during certain hymns or portions of the liturgy for which his presence as "worship leader" is not needed. Certainly there is no bodily indication in such cases of being in the presence of the Incarnate, Risen Christ when at worship.

The widening of the liturgical rift between low and high is therefore making the distinctions more telling than they once were. The vengeance with which "low" worship is now being practiced, as well as the depths to which "low" has in some cases plummeted, leads us to the temptation to wonder how far in fact low now is from the bottom, that is, from the absence of worship at all. Have their efforts to distance themselves from the naughty Lutherans resulted in a reaction also against what is noble and good about traditional Lutheran worship? Put otherwise, perhaps we are drifting to a choice between high church and no church. A sad result, that, of attempts to fend off the naughty, who in fact are already long gone.

Adopted from an article published in June 1994

Friday, May 12, 2006

Lutheran Bingo

It occurred to me in one of my less sane moments earlier today that there is an uncanny similarity between Bingo and the Lord's Supper as they are commonly perceived in our Lutheran circles today; this is especially so when one considers also how Bingo and the Lord's Supper are traditionally perceived in Roman Catholic circles as well. Casual observers might be somewhat inclined to assess Lutherans as wanna-be-Catholics when they observe our church services and practices: we use the same Western Liturgy, but with apologies and uneasiness over it, and when it comes to the Lord's Supper, sad to say, our churches and pastors are less inclined to see it as the Reforming fathers saw it. We speak of the body of Christ being "in, with, and under" the elements, without really knowing what we're talking about. It is doubtful that too many of us mean what was once meant by "under", namely "under the form of", for that sounds too much like (dare I say the "T" word?) . . . transubstantiation. No, that's Catholic, we must steer clear of that. So we find ourselves more comfortable with a host of Reformed explanations of "real presence" which accomodate reason a lot better than that old Thomistic jargon. Transubstantiation, to be sure, is far from the last word on the matter. But I’d take it any day over the rampant receptionism in our midst. Some even speak (dreadfully) in our circles about the elements as nothing more than "vehicles" for the body and blood of Christ. We try to distinguish ourselves from the Reformed on this, but it seems we can't bear to come off like those Catholics, so we come up with flaccid disclaimers.

Now Bingo is much the same way. In the Reformed tradition, Bingo is simply out. Verboten. Anything which even looks like gambling, even if it isn't, is to be shunned. It’s guilt by association. And more importantly, Bingo is, as everyone knows, too, well, Catholic.

But then there are these Lutheran churches, which (to that casual observer) are sort of second-rate Catholic, sort of wanna-bes. And so, true to form, they do, wouldn't you know it, have Bingo in Lutheran churches too. Sort of. There is Bingo there, at their Parent-Teacher League social events, and at their church picnics, and at their annual Thrivent (formerly AAL) parties. But of course, it isn't gambling. That, they are quick to say, would be too Catholic. So we do it without the money. Actually, though, come to think of it, we do even use money sometimes, as in the Thrivent parties, but only as "prizes" to winners, never as a return on a gambling investment.

So in short, Bingo is rather like the Lord's Supper as we have, alas, come to think of it in Lutheran churches. It’s Catholic style and Evangelical substance. We say it isn't really gambling, in the former case, and we say it hasn’t really changed into the body of Christ, in the latter (because that’s too close to transubstantiation for comfort). So we come off as pretenders. Just wanna-bes, second-rate Catholics.

I mean, if you really wanted to get some Bingo action, which church would you attend? So to all you who tremble at the notion of being too like those Catholics, I ask: if someone really wanted to get the body of Christ, would he be likely to attend a church which took such great pains to distance itself from those Catholics on the Body of Christ?

Modified from a 1995 article.

Thursday, May 11, 2006

Preliminary Plans for Audio Streaming

I'm going to have to follow up on some ideas we've been kicking around. There's talk among us of having a weekly radio show on the local station, around 25 minutes long. We'd have some talk, music, and maybe a little preaching.

In the meantime the idea was raised of doing some audio streaming for this site, or perhaps for the St. Paul's site, or maybe for another, new blog. This is all rather new to me, but I'm told it's not really too difficult to do. Now wouldn't that be cool. People could just tune in and hear what's going on here any time they wanted.

And soon, no doubt, we'd be famous. Just think, you heard about it first, right here. See what a benefit you get from plugging in to Gottesblog?

In the meantime the idea was raised of doing some audio streaming for this site, or perhaps for the St. Paul's site, or maybe for another, new blog. This is all rather new to me, but I'm told it's not really too difficult to do. Now wouldn't that be cool. People could just tune in and hear what's going on here any time they wanted.

And soon, no doubt, we'd be famous. Just think, you heard about it first, right here. See what a benefit you get from plugging in to Gottesblog?

Monday, May 08, 2006

Why Fred Flintstone Can't Sing

Here's one from the archives. From the Easter 1996 issue of Gottesdienst. Brings back memories . . .

A week at "Lutheran" camp is enough for me, thank you. But I must say, the weather was grand, the beach was clean and sandy, the sailing was superb, fishing was relaxing, the kids and their parents (my wife and I) had a splendid vacation a couple of summers ago.

Add to this the fairness of the cost, and one wonders how I could even think of complaining. An all-expenses-paid week at camp in exchange for being the Pastor of the Week there, which includes various and sundry clerical duties, amounts to a rather fair exchange, all in all.

But there was nothing I could do about Fred Flintstone.

The camp has this custom of doing little camp songs, as is common, I suppose, in "Christian" camps who have come to be known for such pap as Noah and his arky arky. But it gets to be a bit much to hear what they've done to table prayers here. Never mind what wonders a week of constant exposure to Luther's table prayers and such could have done for these malleable little minds; the expectations here are geared to the taking of familiar tunes from television and the big screen, and making of them prayers. Like, for instance, singing grace to the tune of The Flintstones theme song. Instead of "Flintstones; meet the Flintstones; they're the modern stone age family" we're supposed to sing, by the same tune, "Praise God; O Praise God; And we thank him for our food" and then bang our hands on the table; thence continuing with similar words in place of "From the town of Bedrock, etc." At the close of this "prayer" the campers shout (what else?): "Yabba dabba doo!"

Similar adaptations were made to the theme song from The Addams Family (didididum *click click* didididum *click click* didididum didididum didididum *click click* . . .), the Kentucky Fried Chicken ad ("It's so nice, nice to feel so good about a meal, so good about our Father's many blessings"), and several others.

Now what's so bad about that? Just a little fun, right?

My trouble was that I couldn't help but think, during the Flintstone thing, about a big bronto-burger hanging out the window of my car, and that silly little polka-dot getup that Fred always wore more religiously than I wear a round collar. Or worse, that the kids here might start actually behaving like Junior Addams. And my old fuddy-duddy backwards thinking mind kept asking me, "Is this prayer?"

The answer is clear, of course, which is why I chose, like an old stick-in-the mud, to refrain from singing along. Perhaps no one noticed, but then again, perhaps it would have been good if they had; if they had seen that the pastor here doesn't pray like this.

But why not?

The greater question is, I have come to realize, why they do seem to insist on praying like this. The answer, I have also come to believe, is a rather unsettling one.

Christian freedom, they would undoubtedly affirm.

We, they would likely add, are free in Christ; free from the law and its constraints. Therefore when the law tells us that we must behave a certain way, we demonstrate our freedom from it by behaving in a way that is inimical to that way. See, we are free! such behavior would seem to say. And look what fun it is to pray this new way: we can bang on the table, sing fun little ditties, and have a ball, all the while saying that this is our version of praise to Jesus.

It all sounds increasingly familiar in our midst, in varying degrees and called by various names.

It is unsettling because it is frankly not Christian freedom at all. I was troubled not only by the preponderance of focus on the law and commandants in the little songs, as always happens with fundamentalist guitar songs, but also by the rather clearly evident indications that these people were not really praying here at all; they were just having fun. Thus freedom is freedom from prayer, freedom from the Word, freedom from Christ. Such freedom is not Christian.

But someone may say this assessment is unfair; perhaps there were some who were earnest about their thanks and praise in such an unlikely format. If so, what does this say of the God to whom they are praying? What are the not-so-subliminal implications here? That God is no deeper than Fred and Barney; that Christianity is finger lickin' good and nothing more. There is an element here which is seriously malevolent to the Christian faith. It is the spirit of antichrist, says the apostle John, which denies that Christ is come in the flesh. The flesh alone, as we all know, is complicated. The incarnation is beyond comprehension. That the infant Child feeds the ravens when they cry calls for no other response than the bending of the knee, as the magi did. If at the name of Jesus every knee shall bow, who are we to substitute the snapping of every finger? Or were the magi fuddy-duddies too?

The bottom line here is that Fred Flintstone cannot sing the praises of God; he was not created in God's image. He is a cartoon character, created to entertain. And we, who have all seen his two feet peddle his coupe across our screen, were not created to be entertained. Being entertained is, to be sure, part of what we affirm as Christian liberty; but Christian liberty springs forth from the Gospel and its liturgy, which are from God. Let Christian liberty invade this territory and it will finally be lost.

Thursday, May 04, 2006

Why ceremony?

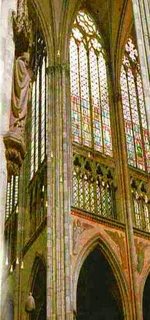

On second thought, rather than merely directing you to our church's newsletter (if you do want to see it, click here), I think I'll just post the lead article here for your consideration. And take a look at this picture. What, eleven servers? Nice. Anyhow, here's the article:

Why Ceremony?

IN THE COURSE OF human events, there come various occasions during which the use of ceremony, that is, of formality in proceedings, is called for. Great ceremony attends the President=s annual State of the Union address, for example. He is announced with great pomp: Ladies and gentlemen, the President of the United States! and everyone rises and applauds, as he moves toward the podium for his address. This always takes a few minutes, because he must shake hands with the people in the aisles. Then, when he finally arrives at the dais, the applause finally fades, and then the Vice President, who is presiding at this joint session of Congress, speaks first, saying something like: It gives me great pleasure to introduce to you the President of the United States! Cor something very similar; something very similar, in fact, to the words of the person who had shouted out the president=s first introduction moments earlier. And then everyone begins to applaud all over again, and sometimes for a very long time. One might wonder why all this has to happen every time the president gives this address. After all, everybody in the world knows who he is, yet here he is introduced twice. The reason for all this, then? Ceremony, of course. Ceremony dictates that certain occasions need great formality, either because of who is present, or because of the moment of the occasion, or both. People tend instinctively to understand the necessity for ceremony at times.

Strangely, however, of late there has arisen a startling lack of ceremony in Christian churches everywhere. This is troubling, for it belies a lack of understanding not only of ceremony=s place, but of the reality present in the Mass. Certainly, if we understand the need for ceremony when the President is present to speak to the nation, how much more ought we to understand the need for it when Christ Himself is present to speak to His holy Church! Could it be that those who wish to make the Divine Service informal fail to realize that worship in Spirit and truth is indeed an occasion in which Christ enters the holy place, opens His holy mouth, and speaks? Not only so, but He really sits among us, on the altar, in the Sacrament.

Consider for a moment which kinds of churches have greater ceremony, and which tend to have less: those whose worship would be considered very formal and ornamentedCRoman Catholics, High Anglicans, Greek Orthodox, and some LutheransCall hold something very much in common, in spite of the differences between them: they all share a profound belief that the Sacrament is no symbol or representation, but really and truly is the body and blood of Christ. But the churches which of late have preferred a more folksy style, or even a style full of the trappings of entertainment (clowns, balloons, rock bands, flashy Gospel choirs, costumes, etc.) tend to be Baptist, Methodist, Presbyterian, and, sadly, some Lutherans. In these churches there is, not surprisingly, also a shared belief that the Sacrament is nothing but an extra, a symbol of some kind, or simply an ordinance of God, whose motions we must go through for no other reason than that He said we should. Even in the Lutheran churches where such tomfoolery is found, there is always, upon investigation, a woefully weak understanding of just what is meant by This is my body.

If anyone does not share this belief with us, he can easily find a church where the Sacrament is given much lower place, or even omitted altogether. We force no one to believe as we do, certainly; but neither will we be forced to believe anything other than what our Lord says: This is my body.

So let us heed to the admonition of St. Paul in this matter, from the Epistle for Easter Sunday: Christ, our Passover, is sacrificed; therefore let us keep the Feast (I Co 5.7-8). For it does not matter what anyone else may say or believe; we know that Christ here gives us His true body and blood; that Christ Himself is truly present here to give us His divine grace; and that, accordingly, if ever there is a time for ceremony, it is first of all in church.

Wednesday, May 03, 2006

Gottesdienst next issue coming out in June

You want great, concise, sometimes sassy, insightful, never dull, edifying, helpful liturgical material? Subscribe to Gottesdienst today. $22 for two years is really a bargain. If you can't afford that, how about $12 for one year. Four issues a year. Can't beat the price, and can't beat the content. To subscribe, click here.

Oh, by the way, if you want to check out the latest St. Paul's newsletter, you can find that also, here.

Tuesday, May 02, 2006

Keeping the Feast

Recognizing Jesus in the Breaking of Bread

For all the benefits of pondering the Passion of Christ, especially during Passiontide, that in itself can never be considered apart from the knowledge His resurrection. Even though it is salutary to let the Passions stand alone, whether as traditionally read during Holy Week, or as performed by choirs for meditative reflection outside the worship setting, or even as observed in a Passion Play, it is equally as salutary to ponder and muse on the resurrection of our Lord. Much has been said and written about the inclination seen especially among Protestants to give short shrift to the Passion. Their empty crosses are indicative of this tendency, and Lenten emphases are for many the exception rather than the rule. On the other hand, a heavy seasonal dose of Christ’s suffering is traditionally followed by a similarly heavy seasonal dose of His resurrection. Lent is forty days plus six Sundays; Eastertide is 49 days including Sundays. Not only so, each of the Gospels dedicates at least a chapter to Christ’s resurrection appearances (St. John gives us two).

Thus it is helpful to see how this emphasis came to be embedded in the liturgy. The Emmaus Road narrative of St. Luke 24 is informative. The basis of His catechesis on the road is, according to the evangelist, “Moses and all the prophets,” but the basis of His sermon at Jerusalem, where the eleven are “gathered together” is, according to His own words, “in . . . Moses, and in the prophets, and in the psalms.” The addition of the psalms suggests that the setting is now liturgical. Most importantly and significantly, Jesus is now recognized whereas before, He was not yet recognized. In the meantime He had made Himself known “in breaking of bread,” whereupon the Emmaus disciples arose immediately to join the others in Jerusalem. Now Christ appears to them all, proves by eating that it is truly He, and begins to preach. In addition, He makes it clear to these His apostles that “repentance and remission of sins should be preached in his name among all nations, beginning at Jerusalem. And ye are witnesses of these things” (27 to 48 passim).

The implications of this progression of events speak volumes for liturgical worship. The Christian liturgy, with its heart in the Psalter, sprang to life as soon as the risen Lord was recognized. At the very moment of the breaking of bread, “they knew him,” and from that very evening, as soon as the Lord appeared again, He reintroduced the Psalter into the resurrected life of the Church. Hope was lost, now hope is renewed; faith had vanished, now faith is reborn, and all this, because of the incontrovertible evidence before the disciples’ eyes that Christ had truly risen from the grave. The Supper which He instituted just three days prior is now celebrated anew by His own direct leading of it as Celebrant. Indeed this renewal He had Himself predicted: “I will not drink henceforth of this fruit of the vine, until that day when I drink it new with you in my Father's kingdom” (similarly in St. Mark 14:25 and St. Luke 22:18). So also, the Psalter, last sung in the upper room (referenced in St. Matthew 26:30 where the disciples after the Supper had “sung a hymn,” most likely a reference to all or part of the Hallel, which are the Passover Psalms, 115-118), and last heard on the lips of the dying Lord, now is sung anew by a joyful community of the faithful who are gathered together to eat. Their sorrowing fast was broken when Christ Himself fed them bread. It is in the Acts of the Apostles, also written by St. Luke, the term “breaking of bread” was more evidently used for the Sacrament of the Altar, and the term became a primitive term for the Sacrament. The first use of the term is at Emmaus, however. Taken together with the ensuing references it becomes clear that according to the evangelist this too was a reference to the Supper. And so it was that it was the resurrected Lord Himself, on Easter Day, who set the continuation of the Supper He had instituted in motion.

This same liturgical celebration of renewed life, which Christ instituted on Maundy Thursday, and to which He gave second birth in Emmaus, becomes evident in the present day in the Church in the continued celebration of the Supper. The intention of Christ that this be thus continued is indicated by His command that “repentance and remission of sins should be preached in his name among all nations.” The joy of Easter commenced when the resurrected Christ fed His Church in the context of the reborn liturgy of the Psalter. His expressed intention is that it thus continue until His return in glory.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)